Unknown Relative

Artist Statement

My grandfather, Alfonso Farrington, born in Nassau, Bahamas (1921), migrated to Canada during WWII to serve with the Royal Canadian Airforce. After the war, he returned to Nassau briefly before making his way back to Canada as a settler on this Anishnabeg land. Our shared lineage can be traced back to enslaved peoples stolen from places now known as Cameroon, Nigeria, Southeastern Bantu, and the Ivory Coast bordering Ghana—as “property” of the British Empire along with the Indigenous Lucayans that were the original keepers of the Island of Eleuthera. This exhibition, Unknown Relative, is an invitation into one story of colonialism, migration, family, and creative resilience through my paternal grandfather's lived experience.

My grandfather passed away when I was 13. With his death, like many diasporic families, our connections to the Islands of the Bahamas were lost. Over the past twelve years, I have been deeply engaged in exploring this ancestry in an effort to understand complex family histories, mysterious identities, and lost stories that are the results of colonial impacts. Before beginning this research, the gateway to discovering my Bahamian roots was inspired by three impactful genres of visual imagery—childhood influences that act as connective threads throughout my collage and video work.

Afrofuturism, the reimagining of a future filled with arts, science and technology seen through a Black lens, started me on my journey. The aesthetics of this movement include space, the universe, glitter, metallic, elaborate costumes and innovative technologies. As a child, I have remarkably vivid memories of my Dad’s 1970s Afrofuture-themed album covers, specifically “Boney M— Night Flight to Venus.” I would sit by the record player staring at the polychromatic glitter-decorated costumes and imagine myself dancing in them.

Secondly, my grandfather’s cousin, Eric Minns, was a well-known Calypso singer and author in The Bahamas. It is his voice you will hear singing Calypso as you explore this show. Minns also wrote about the diasporic travel of Bahamian migrants to Toronto and the deep history of The Bahamas in his novel “Island Boy.” Both the book and his record were always within arm's reach in my home, and they would transport me to a false imagining of “tropical paradise” somewhere far removed from me.

Lastly, my grandfather was an avid letter writer to family and friends left behind in Nassau. He would save the stamps for me and bring them on visits as small souvenirs of the island I’d never known. I carefully arranged them in my childhood scrapbooks, marvelling at these tiny iconographic images of flamingos, palm trees, pineapples, coconuts, fish and shells.

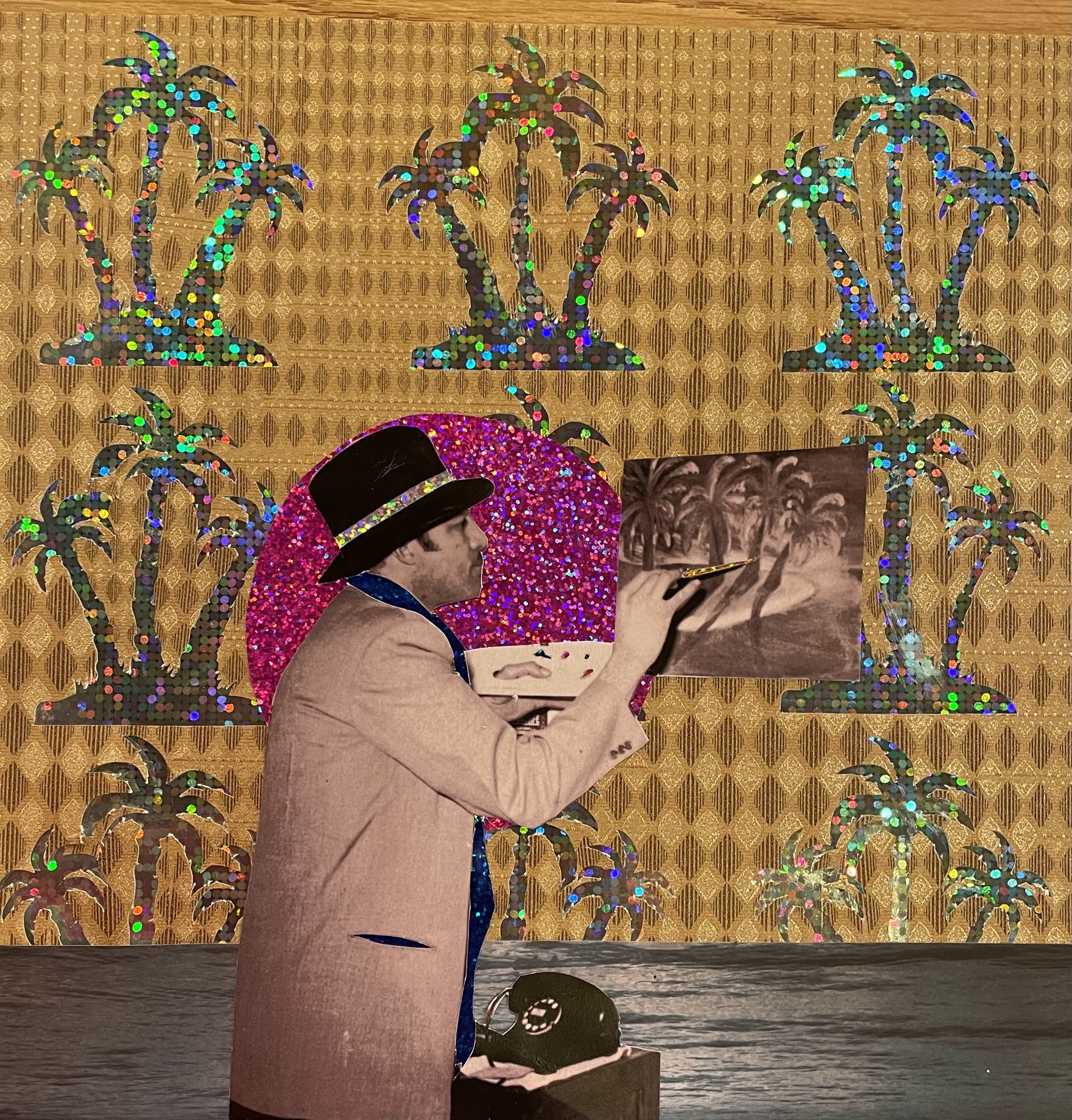

Alfonso was a natural artist his whole life and took this ethos with him to Canada. He was a prolific street photographer whose compositions and captions unveiled his life’s narrative in The Bahamas and Canada. As a mechanic in Cabbagetown, Alfonso would salvage car parts to make wood and metal sculptures. He was also a self-taught painter who made landscapes, living during a period where, as a Black immigrant, he would never have the opportunity to show in a gallery. His paint box is elevated on a plinth in the center of the exhibition.

As an adult embarking on this research, I asked to go through his extensive photo album. When I picked it up, a Victorian Carte De Visite fell out with a Black woman in the photo. On the back in his handwriting were the words “UNKNOWN RELATIVE.” I needed to know who this mysterious woman—devoid of name, time or place—was.

Through online research, I discovered the contacts of cousins in Nassau. Phone chats led to shared images. Archival documents led to family trees. Thus began a journey of unlearning, shedding the false narrative of “tropical paradise” as I unearthed hidden family histories erased by colonialism. Over the last decade, I have travelled to Nassau several times, meeting relatives in person, interviewing archivists, and visiting gravesites to peel back the layers of my family’s past.

I’ve learned in the Bahamas a familiar story for many Afro-Caribbean people. Within the archives, I discovered my Great Great Great Grandfather William Farrington—a British colonist who enslaved 84 people on a sugar plantation—had children with an enslaved woman named Mary. After the death of his British wife Harriet, he moved Mary into the main house and married her. He was “benevolent” towards her and the children he fathered with her and left them all land before his death. The family continued to have interracial marriages throughout the decades in the Bahamas, and many Farrington’s of varying backgrounds continue to live in Nassau.

This led to me reflecting on a myriad of issues anchored in colonial violence so often embedded in the histories of mixed-race people from the Caribbean, including the light-skinned advantage that continues to this day due to the pervasiveness of shadism.

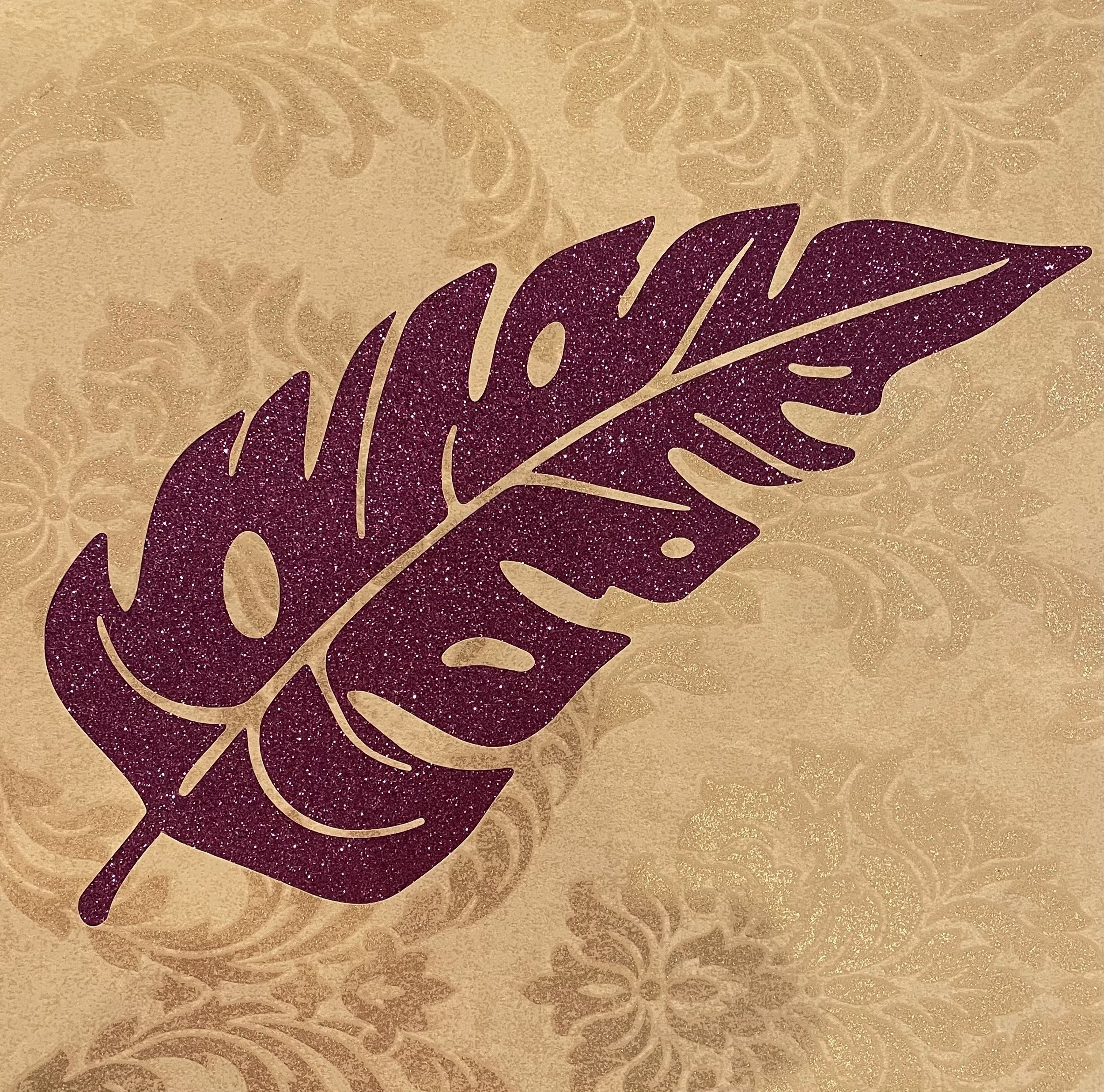

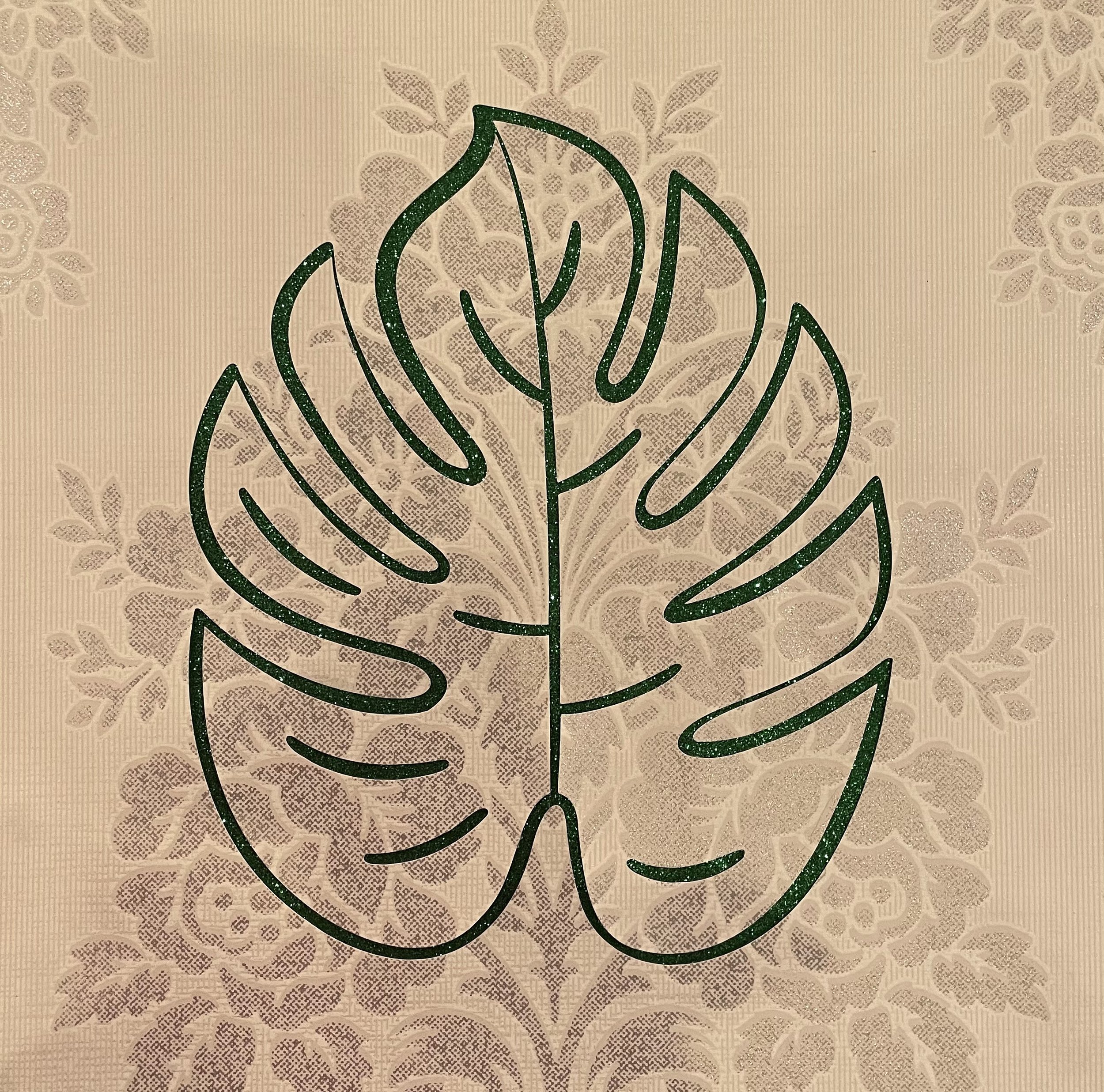

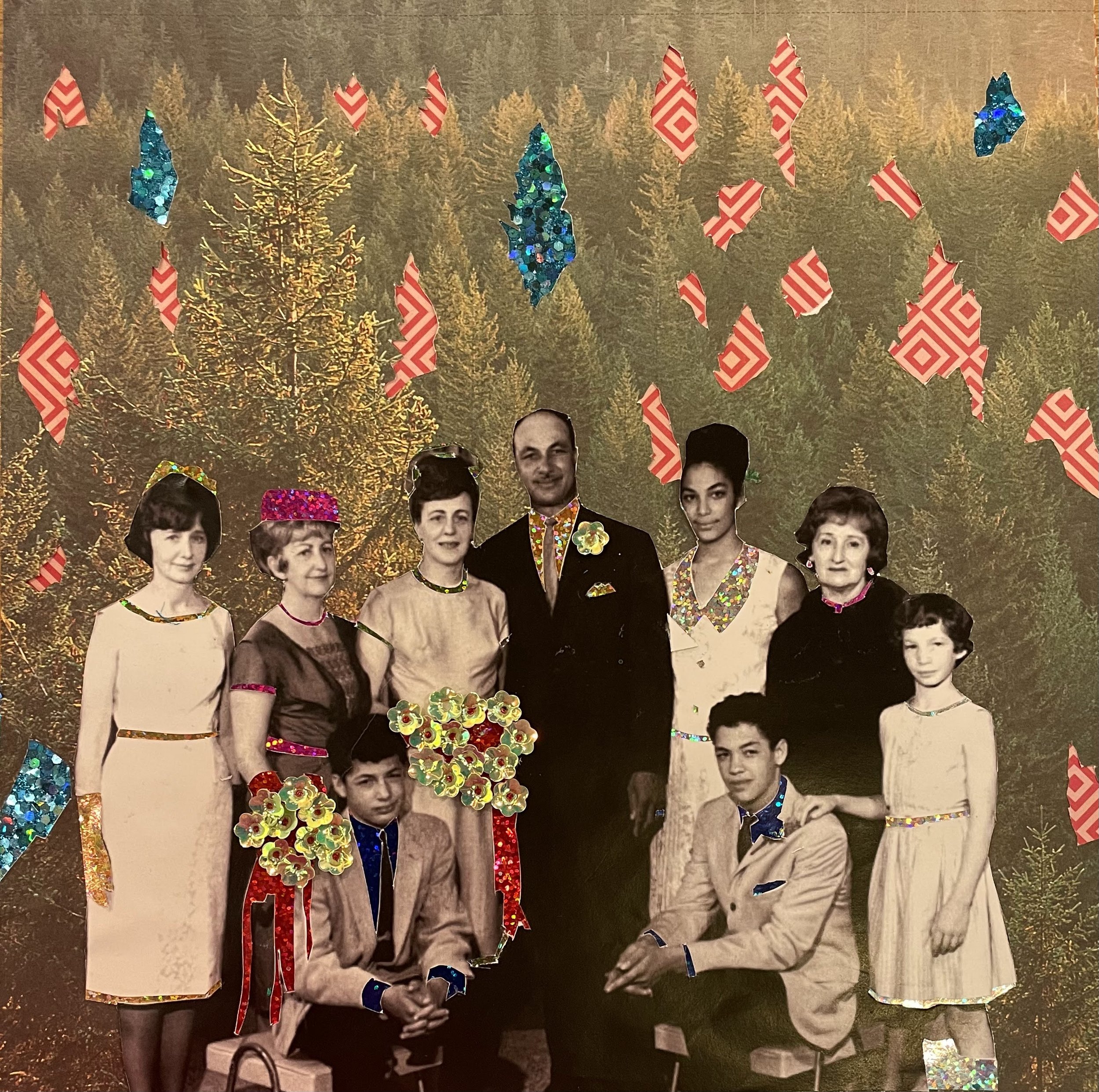

This work began as images in collage form. Using the record album size as an anchor, I intervened with the photos, adding the beautiful and bright colours that I saw in the plants, the people's clothes and the Junkanoo ( John Canoe ) celebrations in the Caribbean. Instead, I wanted to add a celebration of vibrancy and meaning. I added the iconic symbols of plants, fruit and flowers that I had seen on the stamps using the shiny reflective surfaces of those Afro-future aesthetics. I then replaced the staged environments with ocean blues and the pinks from the petal's flowers that permeate the island with sweet floral scents.

I began to cut into Victorian wallpaper motifs displacing the British patterns and resituating our attention on the plants that give life and exist in this natural habitat in the Caribbean. Hanging them on the wall and replacing the negative space with gorgeous glitter in the colours of the plants and the sky feels like an act of resistance.

I strive to create an imagined world where the land is celebrated all around my ancestors, who lived under the rules and societal norms of a place that wasn’t their own. Where the trees, the land, and the water are witnesses to the colonial histories, but offer a future of creative resistance, full of life, hope and imagined and real possibilities.

Return of Slaves Document W H Farrington Page 1

Mixed Media and Microfiche Images on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Return of Slaves Document W H Farrington Page 2

Mixed Media and Microfiche Images on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Long Cay Family Cousins

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Unknown Relative – Candice Merlin Farrington

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 1

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Unknown Relative - Candice Merlin Farrington Older

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 2

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Farrington Family House and Merchant Store West Bay Street Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Great Great Grandmother Alice Dupuch and her Daughters Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 2

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Great Great Grand Father Clarence Farrington and his Sons Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Great Great Farrington Aunties Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Great Grandmother Inez and Children Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inch

Alfonso Farrington One Years Old Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 7

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Grace, Hugh, Alfonso and Family Car Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Great Grandma, Aunties and Cousins Nassau New Providence Island 1939

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Shell Resistance 1

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

George and Hugh Wulff Road 1943

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Alfonso Farrington Age 18 Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Farrington Family Portrait Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 4

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Brothers in Bahamas Defense Nassau Wulff Road

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 5

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Alfonso Body Building 1940 Nassau

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

First Experience with Snow

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Great Aunt Grace Studio Portrait Nassau New Providence

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Great Aunt Grace Wedding Portrait Nassau New Providence

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Cousin Faye Nassau New Providence

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Shell Resistance 1

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Eating Coconut Sandy Cay Bahamas

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Picnic with Moya Fahy Sandy Cay

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 6

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

First Experience with Snow

Mixed Media and VintagePhotography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

His Most Gracious Majesty Called on the Men of his Empire

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

RCAF Brandon Manning Depot 1943

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Snow 30 Below Zero NB Canada

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Overlooking the St Lawrence Quebec City

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Coral Resistance 1 Mixed Media on Paper 12 x 12 inches

Western Road Near Caves with Eric Minns Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper 12 x 12 inches

Keep to Starboard Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper 12 x 12 inches

Magic Shell Resistance 2

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Playing in the Street Cabbage Town

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Trip to the Exhibition

Mixed Media and VintagePhotography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

High Park Sunday

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 8

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Mixed Media and Vintage

Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 8

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Sunny Side Sunday

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Tommy’s Birthday Cabbage Town

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Triny Fahy Catch 1946

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Grace and Peter Farrington Cabbage Town

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Nassau Cousins Visiting Toronto

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Buttonville Airport 1959

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 9

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Peter & Tommy Dora’s Mercury Toronto Ont

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Painting Home

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Second Wedding

Mixed Media and Vintage Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Farrington Family Plot 1839 Western Cemetery Nassau New Providence Island

Mixed Media and Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Plant Resistance 10

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Self Portrait with Shadow of Palm Leaves

Mixed Media and Photography on Paper

12 x 12 inches

Magic Conch Shell Resistance 3

Mixed Media on Paper

12 x 12 inches